Introduction

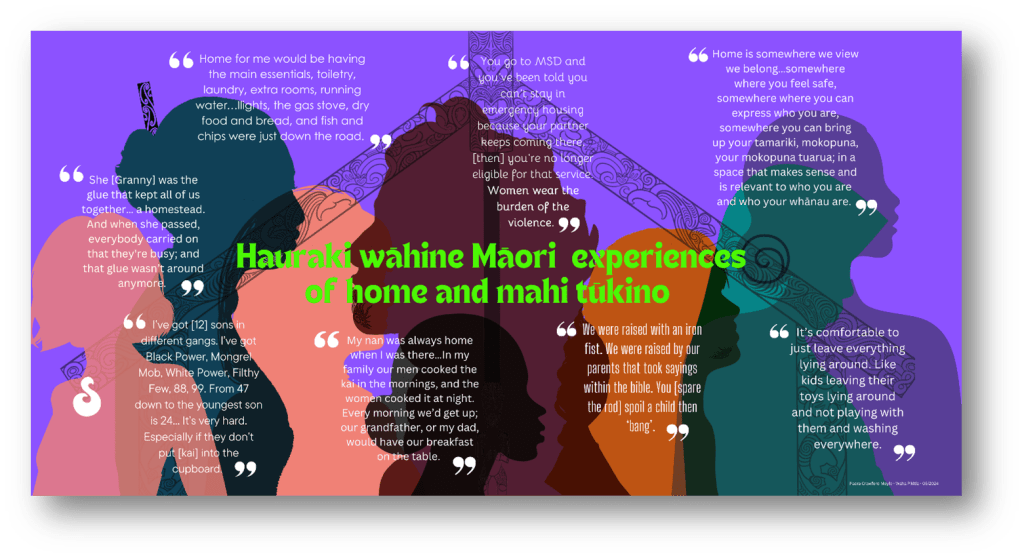

Eight wāhine Māori from Hauraki shared their realities about home, safety, and survival as part of “Tō Mātou Kāinga, Tō Mātou Ūkaipō” (2022-2024) research project. Despite their crucial insights, and at the time of writing this article, their voices have not featured in the project’s outputs. Therefore, this commentary centres on their lived experiences, analysed through the Pū-Rā-Kā-Ū framework (Wirihana, 2012), to reveal what home truly means for wāhine experiencing both mahi tūkino and housing insecurity.

All eight wāhine were mothers, with five being grandmothers and three great-grandmothers. They lived in temporary housing, whānau whenua, caravans, cars, and private rentals. Five were connected to gang whānau. All shared experiences of systemic discrimination and, for most, the trauma of having tamariki removed by the state.

Pū (Source): The Desire for Kāinga

For these wāhine, home transcends physical shelter. As one explained:

“Home is where you feel security, home is what you put into it, you get out of it. It’s where you can invite people in and see them go. It means everything, your independence… Home is where my children, my grandchildren should be. But that hasn’t happened. I thought when I got older, my moko would come home and just be part of my world, but that’s not what happened. I still long for that.”

Another emphasised cultural belonging:

“Home is somewhere we view we belong… somewhere where you feel safe, somewhere where you can express who you are, somewhere you can bring up your tamariki, mokopuna, your mokopuna tuarua; in a space that makes sense and is relevant to who you are and who your whānau are.”

Some wāhine describe intergenerational connection to whenua:

“When I think of home, I think of my nannies, my pāpā, all of us living together on the whenua. I think of our men cooking the kai in the mornings, our mothers looking after the whare at night. We had fruit trees, gardens, the river right there.”

These connections to whenua and whānau have been disrupted by colonisation and bureaucracy:

“We had land. It was ours, given down, but then the council put their own boundaries, and now nothing lines up. They put us at war with each other. We were supposed to have a right to our land, but when we tried to go back, our own cousins told us we didn’t belong. It’s heartbreaking.”

For some, home has become a site of exclusion and trauma:

“I’d love to go home, but I can’t. I hold the secret that blew everything open. I am vilified.”

Others describe how state intervention forced them into constant movement:

“Home could be, had been nomadic. I was always moving. I didn’t want OT or the Police to find me. I was just trying to keep my boy with me. That meant home was wherever we could rest, where we weren’t going to get moved on, where I didn’t have to look over my shoulder.”

Rā (Enlightenment): Connection and Systemic Barriers

Wāhine describe how government systems create barriers rather than support. They face discrimination when seeking housing:

“Māori women and children. They’re all going to be sleeping on top of one another. Like they’re vermin, rabbits.”

This prejudice intensifies when they seek safety from mahi tūkino:

“If I write a support letter saying they’ve been in refuge, there’s another bias there. What does that mean? Are they going to be bringing a violent partner like a rabid dog?”

Social welfare services often punish wāhine for the violence they have endured:

“You go to MSD and you’ve been told you can’t stay in emergency housing because your partner keeps coming there, [then] you’re no longer eligible for that service. Women wear the burden of the violence.”

The State’s removal of tamariki from their mothers represents a particularly devastating form of colonial harm, with racial discrimination evident in practice:

“This woman had tried and tried. There were no family violence issues. It was a case of having to live on a bus. She was doing the best that she could. Right next to her, an older white couple lived in a bus and OT didn’t disturb them. But they were all over this Māori woman and her seven tamariki.”

Five of the wāhine described being connected to gang whānau, creating additional layers of discrimination:

“I’ve got [many] sons in different gangs. I’ve got Black Power, Mongrel Mob, White Power, and Filthy Few. From 47 down to the youngest son is 24… It’s very hard, especially if they don’t put [kai] into the cupboard.”

Wāhine emphasised that gang members are “whānau too” and described healing efforts within gang whānau to break intergenerational trauma. However, gang connections led to exclusion from support services and mistreatment by agencies including Police, MSD and OT. Many described living in a constant “flight or fight mode,” leaving them emotionally “numb” and “shut down.”

Wāhine clearly identify how systems profit from Māori suffering:

Some wāhine describe violence as a pattern across generations:

“That’s how they get our kids. They made Māori their job, so they could get a job.”

The impact is profound:

“The system nearly broke her. The system. That’s what we are. We’re the buffer for that.”

Kā (Past, Present, Future): Wairua and the Journey Through Violence

For many wāhine, home was a site of violence:

“Home is unsafe. Home is unsafe. The children are unsafe. There is no wellness. There’s no feeling safe or well. Just surviving.”

“In my whānau, generations and generations. There’s a great grandchild being born. Her partner of 40 years, their son treats mum the same way dad does. He goes off to jail and then the son steps up and he’s the man of the house. Walks all over mum, takes over.”

Religious and cultural influences shaped the way many wāhine were raised:

“We were raised with an iron fist. We were raised by our parents who took sayings within the bible. You [spare the rod] spoil a child then ‘bang’.”

The loss of elder family members often marked a critical disruption in family cohesion:

“She [Granny] was the glue that kept all of us together… a homestead. And when she passed, everybody carried on that they’re busy; and that glue wasn’t around anymore.”

When wāhine defended themselves, they were criminalised:

“It’s one of two things. Compliance or fight back. If they’re fighting, they fight for their lives. They’re in a corner mostly. We’ll get a phone call from the police, she’s the perpetrator, and what did she do? She pulled a knife on him. And what was he doing? He’d just hit her over the head with the jug.”

Many wāhine lived in constant movement seeking safety:

“A home for me was on the road and moving around. So, there was no specific space that was my own. Home was often the sky, and wherever I lay down, escaping what was going on.”

Even after leaving, the physical and emotional effects of violence remained:

“Even after I left, I still flinched at loud noises. I still had that feeling in my stomach when a car pulled up outside, thinking it was him. It takes a long time for your body to realise that it’s over.”

The cycle of leaving and returning trapped many:

“One woman came in on the 18th time and that was it. She’d finished.”

Justice systems failed to recognise verbal abuse and psychological control:

“The information out there doesn’t support that you can get space in a safe house if you’re getting verbally abused. We get a call, ‘I think I’m going to kill my husband today.’ Okay. Do you want some help?”

Ū (Sustenance): Returning to Ūkaipō and Healing

The journey toward rebuilding home emerges in wāhine narratives as a gradual process. After years of living with the consequences of intergenerational trauma, safety feels unfamiliar:

“It’s strange when you’re so used to waiting for something bad to happen. The first few weeks, even in the safe house, I was still sleeping with my shoes right next to me. Just in case. You don’t realise how much your body has learned to be prepared for anything, always ready to run.”

Small moments mark the beginning of healing:

“The first time I had a proper shower, I just stood there for ages. I wasn’t rushing. I wasn’t listening out for footsteps. I just stood there in the warm water, and I cried because I couldn’t remember the last time, I had a shower that wasn’t filled with fear.”

Years of control strip away basic autonomy:

“It’s funny. I didn’t realise how much I’d been conditioned to ask for permission. The first couple of weeks, I kept asking, ‘Can I make a cup of tea?’ ‘Is it okay if I sit here?’ I didn’t even notice I was doing it. It wasn’t until one of the other women in the house laughed and said, ‘Sis, you don’t have to ask, just do it,’ that it hit me.”

Reclaiming home means establishing personal authority over space:

“I never got to decide what went on the walls, what furniture we had. Even my clothes, he picked for me. When I finally got my own place, I didn’t know where to start. I just knew I wanted it to be mine. So I started small. I bought a yellow pillowcase.”

For some wāhine, particularly those who had experienced chronic violence resulting in health issues, aspirations for home were modest but profoundly meaningful:

“Home for me would be having the main essentials, toilet, laundry, extra room, running water…lights, the gas stove, dry food and bread, and fish and chips just down the road.”

Others emphasised the importance of traditional family roles and routines that provided stability and nourishment:

“My nan was always home when I was there…In my family, our men cooked the kai in the mornings, and the women cooked it at night. Every morning we’d get up; our grandfather, or my dad, would have our breakfast on the table.”

After years focused only on survival, dreaming about the future can feel impossible:

“When I’ve talked to a couple of women, they go, ‘Dream of home, what’s that?’ I have to talk to them more about if you were just seeing yourself doing something different in the world, what would it be?”

Reconnection to whenua represents a disruption of colonial separation:

“I thought I’d never be able to go home. But I did. I’m back on my whenua. And I never thought I’d be able to say that.”

What This Means

This article exists because the voices of Hauraki wāhine were excluded from outputs of a project that claimed to represent their experiences. By centring their pūrākau, we correct this and honour their expertise about Māori conceptions of home and safety.

These wāhine show that home encompasses cultural identity, intergenerational connection, and the right to belong. Their narratives reveal how government systems often work in concert to entrench rather than alleviate housing insecurity.

Their insights challenge housing policy to centre Te Tiriti o Waitangi obligations, recognise the connection between mahi tūkino and housing instability, and support both immediate safety and long-term cultural connection.

Most importantly, their voices remind us that those with lived experience hold essential knowledge about solutions. As one wahine powerfully stated:

“We know what we need. We’ve always known. The question is whether anyone is actually listening.”

As Te Whāriki Manawāhine O Hauraki researchers, we are committed to ensuring our whānau voices are heard. These wāhine hold both the knowledge and the solutions needed to help transform how we understand kāinga.

_________________________________________________________________________

Paora Moyle, Director of Research at Te Whāriki Manawāhine O Hauraki.