The dire housing shortage in the Hauraki region has created a crisis for whānau Māori. The severe impact of whānau violence and systemic entrapment forces many Wāhine Māori and their tamariki into homelessness. Wāhine seeking support face significant challenges in finding suitable and sustainable housing, which can force them back into the violent situations they were trying to escape. Despite these intersecting, persistent, systemic and structural obstacles, their hope for a long-term housing solution fuel their determination and courage to strive for a new beginning.

In response to this crisis, the He Whare, He Taonga housing project emerged, envisioning a future where tamariki are raised in non-violent villages founded on mātauranga me tikanga Māori. Villages where Wāhine Māori and their whānau are fully supported to recover from their lived experiences of mahi tūkino, and they are thriving.

At the heart of our work was a fundamental commitment: to amplify the perspectives of Wāhine and whānau affected by the intersection of whānau violence and housing poverty. Recognising the historical silencing of Wāhine, our research team deliberately departed from conventional research methodologies. We sought approaches that would ensure these often-marginalised perspectives remained front and centre throughout our work.

This commitment led us to develop three new Mana Wāhine methods: the ‘Peke Pepa Paraone’ (brown paper bag) as a process guide, ‘Waha Pikitia’ as a depiction guide, and adapt ‘Pū-Rā-Kā-Ū’ as an analysis guide. Through these methods, we discovered that in amplifying the experiences of Wāhine, we also connected with “the voices of their ancestors: their stories… create the space for inviting and re-engaging with all the voices and echoes of the past, the present, and the future.”

This account focuses on the first of these methods: the Brown Paper Bag methodology. What began as a pragmatic solution to a temporary shortage of research materials evolved into a meaningful metaphor and methodological framework. The brown paper bag became both a practical tool and a meaningful symbol that helped us understand how to conduct research in ways that truly serve communities facing housing poverty.

How Te Peke Pepa Paraone Method Emerged

The brown paper bag appeared multiple times throughout our research journey, not by design but by chance and necessity. When usual research materials weren’t available, we took apart brown paper grocery bags to create writing surfaces. This practical solution became a meaningful symbol for our whole research approach. It showed us the value of using what’s available, adjusting to circumstances, and finding value in what mainstream society often overlooks.

As our CEO reflected:

“I went to the supermarket down the road to buy some flipcharts, but they didn’t have any. I bought some kai and other stuff, and, walking back to the car with my brown paper bags, I thought we’ll pull these apart and use them. You have to be open to the possibilities, opportunities, and options and to the obvious and the most appropriate answer at that time.”

This moment of practical problem-solving became a meaningful metaphor that guided our entire research process.

Key Meanings and Applications of Te Peke Pepa Parone

What makes the brown paper bag methodology so rich is its multiple layers of meaning, each of which speaks to different aspects of conducting research with Wāhine Māori:

Strength and Resilience in Research

The physical properties of the bag itself symbolise the resilience of our participants:

“Even now as I touch the paper bag it’s a lot stronger, its substance feels solid like it could take a beating, sorry for the use of that pun [laughter]. We pulled them apart and they naturally became a part of our wānanga and our kōrero.”

Unlike fancy academic papers or rigid research frameworks, the brown paper bag represents something that lasts despite hardship. This mirrors the strength of Wāhine who continue to care for their tamariki despite facing housing poverty, violence, and discrimination.

Versatility and Transformation

The bag’s ability to change from container to writing surface mirrors how knowledge and stories can be reshaped and reused:

“The bags were transformed from holders of goods to useable parchment for documenting and navigating our thinking.”

This transformation challenges conventional research methods that remain rigid and fail to adapt to participants’ lived experiences. The paper bag offers freedom of expression without the constraints of academic formats or standardised questionnaires.

Protection and Safety

For some participants, the brown paper bag represented protection:

“Before the black polythene bag, the paper bag is what we as kids in state care carried our worth around in as we were trucked from placement to placement. The bag held all of that, and in some ways for a while, it protected the sum-total of a child’s worth.”

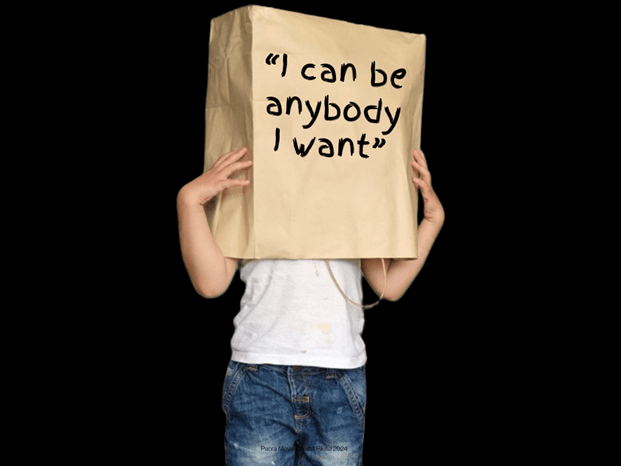

We witnessed this protective quality when a young boy with autism at a safe house wore a paper bag as a mask, saying, “Oh, I can be anybody I want, and you can’t see me.” The bag became a place to speak from or hide in, a metaphor for creating safe spaces within research where vulnerable truths can be shared.

This insight reveals a deeper understanding about trauma-informed research practices. For Wāhine who have experienced violence and displacement, conventional research methods can feel invasive and retraumatising. The brown paper bag concept acknowledges that participants need to control what they reveal and when they reveal it. Just as the young boy could look out through his mask while remaining unseen, research participants must be able to share their experiences from a position of safety and control.

Traditional research methods often require participants to expose their trauma in ways that can feel unsafe or exploitative. The brown paper bag approach recognises that true knowledge emerges only when people feel safe enough to share it.

Simplicity and Accessibility

The bags represent a return to simpler, more accessible approaches:

“The brown paper bag takes me back to childhood when things were a lot slower. It’s the childhood connection and connection to the past. It’s a different world today, so busy and complex.”

In a research world full of complex methods and jargon, the brown paper bag approach calls for simple, usable tools that ensure research serves communities rather than academic careers. There is something about the brown paper bag approach that for many Māori means just using simple tools, using what we already have or what we can afford, nothing flashy. As one participant reflected, “I don’t need a million dollar mansion, just a roof over my babies’ heads.” This speaks to the heart of the housing crisis and the practical solutions that communities need.

Historical Context and Resistance

Our team also acknowledged the painful history of the “brown paper bag test” used to discriminate against darker-skinned African Americans:

“When we didn’t have the white flimsy paper, we got the hardy brown paper. It represents the participants because at another time the brown paper bag was used as a test of skin colour; if you were darker than the bag held to your face then you were excluded from privileged spaces.”

By using the brown paper bag as a symbol of Indigenous research methodology, we recognise this history while changing its meaning into one of inclusion rather than exclusion.

This awareness of the bag’s complex history reminds us that research tools always exist within historical and cultural contexts. For Wāhine Māori, who have experienced exclusion from housing based on intersecting factors of gender, ethnicity, and class, the brown paper bag methodology transforms tools of exclusion into tools of inclusion.

Comparing Brown Paper Bags to Colonial Research Methods

The team drew a contrast between the brown paper bag and plastic bags, likening the latter to colonisation:

“In comparison, the plastic bag is a hangry [hungry and angry] item, meaning it consumes more than it can safely carry. It’s an imposter; in the water, it appears as a jellyfish, and it is the number one killer of the Blue Whale. That’s colonisation, something that presents as good for you, slowly chokes you to death, and takes 400 years or more to break down.”

This metaphor captures how conventional research methodologies often present themselves as beneficial to communities while actually extracting knowledge, imposing external frameworks, and ultimately causing harm.

The Brown Paper Bag Method in Practice

The brown paper bag method centres community needs through several practical principles: it carries what matters to communities, adapts to changing circumstances without breaking, uses accessible tools that don’t require special expertise, creates safe containers for difficult narratives, and remains open to transformation. As one researcher noted, if a paper bag is too overburdened, “the bottom falls out of it,” reminding us to be attentive to the weight we ask participants to carry.

Working Within the Mana Wāhine Framework

The brown paper bag methodology operates within a Mana Wāhine framework that “allows us to move between these spaces to challenge, navigate, rediscover, and articulate our Wāhine tīpuna ancestry.” This approach recognises that Wāhine Māori are the experts in their own lives and should be key contributors to housing solutions. It insists that the perspectives of those most affected by housing issues must be centred in developing responses. In this framework, research itself can be an act of reclamation when it enables Wāhine to “write ourselves back into our herstory.” Solutions emerge from Indigenous knowledge systems and practices, not from imported methodologies.

What This Means for Future Community Research

This approach challenges researchers to examine what their methodologies symbolise and whether they are as accessible and resilient as a brown paper bag. It prompts us to consider if our approaches extract or empower, and whether our research allows participants to safely carry their experiences or forces them to leave important parts behind.

As our team reflected:

“There is something in this korero that speaks to me about a return to a system that is simple and accessible, usable, resourceful, and multi-purpose; it’s a descriptor of where we might go with our solutions. Whilst we use the paper bag analogy to help sort our thinking our wānanga and our ideas, I think too it has a place in our solutions. We can reuse it [the approach] and recycle it again and again.”

For Wāhine Māori facing housing poverty, sustainable research means creating processes that build community capacity rather than dependency on external researchers. Knowledge creation should be cyclical and regenerative, like the paper bag that can be refolded and repurposed.

Simple Tools for Change

The brown paper bag approach reminds us that “the answers we seek can be right in front of us.” It challenges the idea that good research needs complex tools, suggesting instead that effective approaches might be as simple and adaptable as a brown paper bag; able to hold difficult truths with care and centre the wisdom of those traditionally silenced.

For Wāhine Māori facing housing poverty in Hauraki, research conducted in ways that centre their experiences can lead to housing solutions that actually work. The method shows that research should contribute to solutions, not just document problems.

As we reflect on the brown paper bag as a research approach, we are called to examine whether our research practices extract from communities or contribute to them, whether they impose external frameworks or grow from community wisdom. The humble brown paper bag challenges us to create research that is as accessible and transformative as its journey from grocery container to symbol of decolonised knowledge creation.

Reference

Te Whāriki Manawāhine Research. (2024). He Whare, He Taonga Report. Te Whariki Mana Wāhine o Hauraki. Thames, Aotearoa.

Paora Moyle (Ngāti Porou), is Kaihautū Rangahau at Te Whāriki Manawāhine Research. For more information about Te Whāriki Manawāhine O Hauraki and our research mahi, please visit our website or contact us directly.