Our research team at Te Whāriki Manawāhine O Hauraki has worked hard over the last 3 years to build our ‘Hauraki Whānau Voices’ research program. We have undertaken four key foundational research projects exploring the experiences of whānau Māori in our communities:

- He Whare, He Taonga (housing poverty and family violence)

- Gang Whānau Healing from Intergenerational Trauma (systemic discrimination)

- Voices of Takatāpui Rainbow and MVPFAFF Survivors (intersectional challenges)

- Hauraki Māori Weathering Cyclone Gabrielle (crisis response gaps)

A consistent finding across all our research has been that wāhine Māori disproportionately bear the burden of violence, both in their homes and through their interactions with community agencies and services.

We’ve clearly shown that the burden becomes even heavier for wāhine with intersecting identities. Those who are Māori, women, and also from gang whānau or takatāpui, experience what our participants describe as a “multiple whammy effect.” Each additional identity marker increases their vulnerability to violence while simultaneously decreasing their access to effective support.

It was this recognition of the layered, intersectional discrimination faced by wāhine from gang whānau that led me to focus one of our research projects specifically on their experiences. Our mahi highlights how these wāhine are healing from intergenerational trauma and reclaiming their narratives.

“Ki ō matou ake kupu…”

Gangs in Aotearoa have evolved over four to five generations into distinct gang whānau, with mokopuna and mokopuna tuarua born into them. These whānau are among the most marginalised and discriminated-against communities in Aotearoa.

There is no good reason for any of us to be applauding the way gang whānau are treated, especially in light of the Abuse in Care Royal Commission of Inquiry findings, which showed that 80 to 90% of Māori gang members experienced abuse in state care. The sixteen volumes of survivor pūrākau, completed in 2024 after seven years of inquiry, clearly lay out what needs to change. They reinforce what has long been known; state interventions designed to force tangata whenua into becoming model white-is-right citizens do not work.

Yet, despite the Commission’s powerful testimonies and recommendations, the current government is ignoring them while actively dismantling protections for whānau Māori and attempting to erase whānau identity. In between, it is profiteering from conveyor-belted whānau misery.

Negligent legislation, such as the repeal of Section 7AA of the Oranga Tamariki Act, removes state obligations to uphold tikanga and support whānau-led solutions, making it easier for tamariki to be removed from their whānau and institutionalised in desolate facilities. This is the well-oiled machinery of systemic racism.

These genocidal policies do not exist in isolation. Across the world, Indigenous communities face the same state interventions designed to break whānau connections and erase Indigenous ways of knowing. The forced removal of Indigenous children in Australia, Canada, and the United States echoes the ongoing dislocation of tamariki Māori today.

Additionally, the new government’s “get tough on brown crime” policies target gang whānau through increased surveillance, restrictions, and fashion policing, rather than addressing the white supremacist attitudes and systemic inequities that sustain colonial oppression. This toxic racism makes us want to scream: “Only those who love our tamariki should make care decisions about them!” And when the state fails as a parent, then lies to cover its incompetence, where is the accountability? Where are the prosecutions, the incarcerations? Nada. And the cogs continue their cyclical churn.

But here’s a spanner in the works: over the last two years, leadership from one gang whānau have been working with Te Whāriki Manawāhine O Hauraki (Te Whāriki) to break the cycle of intergenerational trauma, ensuring it is no longer passed on to their mokopuna. This collaboration is grounded in Te Ara PouTama and PouHine, a Hauraki-based traditional model of healing mahi tūkino that has been operating for over 20 years.

In 2024, I was a recipient of the ‘Rangahau Hauora Māori Emerging Researcher First Grant’ from the Health Research Council to undertake a research project through which wāhine from gang whānau could voice their lived experiences; in their own words. Using Mana Wāhine methodology and pūrākau kōrero, our project illuminates the voices of these women, capturing their healing journeys. They are mothers, grandmothers, great-grandmothers, sisters, partners, and leaders; women who live, laugh, love, and breathe the same air as everyone else in Aotearoa. They work, pay taxes, raise tamariki, plan for the future, and dream of a world where their mokopuna can thrive in violence-free communities.

Like lights along the runway these wāhine are showing us a different path. “We define who we are,” says their leadership. These words ring clear and strong from women who have had enough of others telling their stories, claiming their stories, or profiting from them, like TVNZ1 did recently to four leaders. For years, wāhine from gang whānau have watched as media, academics, and society have painted pictures of their lives that bear little resemblance to their lived reality.

“We are not your data,” one wahine states matter-of-factly to me during our conversations. “We are not your research subjects or your social problems to solve.” This assertion challenges generations of research that has too often treated whānau Māori as subjects to be studied rather than experts in their own lives.

“We are accountable to ourselves” they emphasise. This principal shapes not only their healing journey but our entire research process. It recognises that true knowledge comes from within communities, emerging from both lived experience and ancestral knowing. Guided by the work of Matua Moana Jackson, Mātikite Mai reminds us that true knowing comes from both lived experience and ancestral wisdom that resides in our DNA.

The impact of intergenerational trauma requires healing that grows from within communities. These wāhine understand that their work in PouHine wānanga creates spaces where both personal and collective healing emerges. Through PouHine wānanga, these wāhine are creating their own pathways to wellbeing. This isn’t about outsiders coming in to “fix” their lives. It’s about wāhine Māori supporting wāhine, sharing knowledge, building strength together, and reclaiming their herstory and whakapapa. One wahine describes these wānanga:

“The PouHine has saved my life. I used to carry all the trauma, the anger, the shame. Now I see I was never alone. My tūpuna were always with me, calling me home to myself.”

Our research methodology mirrors this approach, creating space for wāhine to document their own journeys, to share their insights in their own words, and to build solutions that make sense for their daily realities.

The project has one clear purpose: working with wāhine from gang whānau to co-create how their pūrākau are told. While acknowledging institutional requirements, our work prioritises wāhine-led approaches to gathering and sharing experiences. By shifting who shapes knowledge and who tells the story, research itself becomes an act of decolonisation.

This is not just research. This is resistance. This is the reclaiming of wāhine toa, the restoration of mana, and the forging of a future where wāhine from gang whānau define their own destinies. Their stories are no longer told for them; they are telling them, on their own terms, in their own voices, with the full power of their whakapapa behind them. This is sovereignty in action.

Paora Moyle (Ngāti Porou) is the Kaihautū Rangahau at Te Whāriki Manawāhine O Hauraki, working with wāhine leadership from gang whānau to share and document their healing journeys, in their own words.

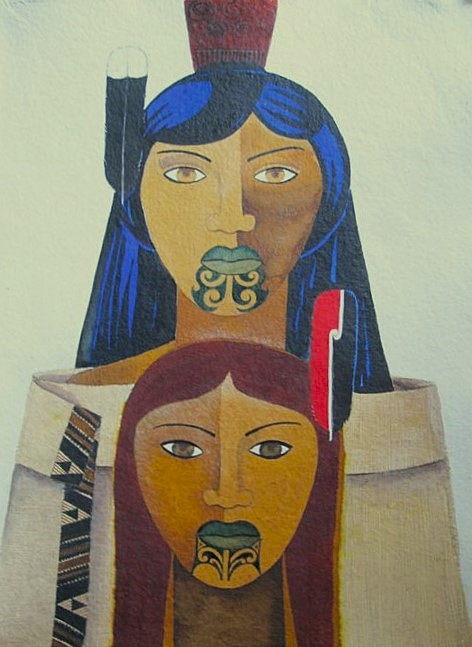

Image with consent from Robyn Kahukiwa (Artist extraordinaire)